Catholic Identity

Catholic Identity

Eastern Catholic churches in our Catholic schools

By Amer Youhanna, Project Officer – Catholic Engagement, Catholic Mission, People and Culture, Melbourne Archdiocese Catholic Schools.

Diversity in the Early Church

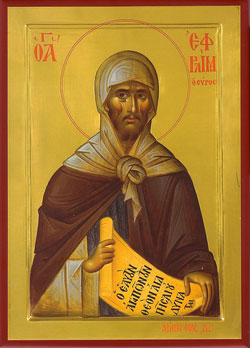

Let books be your dining table, / and you shall be full of delights. / Let them be your mattress, / and you shall sleep restful nights (St Ephrem circa 306–373, cited in 1989).

The memorial day of St Ephrem is held on 9 June. Recognised as a Doctor of the Universal Church (Gorayeb 1921, p. 304), St Ephrem is venerated and respected in all apostolic churches (churches founded from the time of the apostles and/or by their immediate disciples, such as Catholic and Orthodox churches). St Ephrem’s teachings, poetry and theology provide great platforms for ecumenical gatherings held by Eastern churches, but what do we know about Eastern churches?

My personal experience of living in Australia, and in the European countries I have visited, indicates that many people who live in Western cultures know about the Catholic or Reformation churches when speaking about Christianity; however, when most people mention the Catholic Church, they are referring to the Roman Catholic Church. Few people seem to know about Eastern Catholic churches.

A glimpse at the history of Eastern Catholic churches

There has never been a time in the history of Christianity where there was uniformity of culture, liturgy or language (Attwater 1935). The Church from its earliest days had a multicultural nature and has never been designed to be enclosed within a single nation, culture or language. We tend to hear more about the Roman Catholic Church not only because of its sheer size, but also due to the evangelisation of countries explored and colonised by European nations.

This colonial culture of Europe from the Middle Ages influenced the behaviour of some clerics of the Roman Catholic Church and its missionaries. They had the impression that there was a hidden agenda to achieve an eventual Liturgical Latinisation of Eastern Catholic churches. This was not the official approach of the Roman Catholic Church, but ‘it is something, as it were, accidental, to be tolerated in order to avoid a greater evil’ (Sayegh 1963, p. 165). This Latinisation of Eastern Catholic churches was rigorously forbidden by Pope Leo XIII in his apostolic letter Orientalium Dignitas (1894).

Vatican II and the new approach

The Second Vatican Council changed many things within the Church. Among them was the approach of the Roman Catholic Church towards Eastern Catholic churches. There has since been a great amount of support and encouragement to all Eastern Catholic churches for them to do everything possible to keep their inherited traditions.

Orientalium Ecclesiarum is one of the Second Vatican Council’s decrees regarding Eastern Catholic churches, promulgated on 21 November 1964 (Paul VI). This decree has given new meaning to the heritage of the Eastern Catholic churches. ‘The Sacred Council, therefore, not only accords to this ecclesiastical and spiritual heritage the high regard which is its due and rightful praise, but also unhesitatingly looks on it as the heritage of the universal Church’ (n. 5, emphasis added). Therefore, we as Catholic schools ‘should be instructed … in the knowledge and veneration of the rites, discipline, doctrine, history and character of the members of the Eastern rites’ (n. 6).

Eastern Catholic churches in our diverse community

The Eastern Catholic churches with communities in Australia include the Melkite Catholic Church, Ukrainian Catholic Church, Syriac Catholic Church, Chaldean Catholic Church, Syro-Malabar Catholic Church and Maronite Catholic Church (which established the Catholic school Antonine College in Pascoe Vale).

The communities of Eastern churches (both Catholic and others) are very well-known for their strong connection to their parishes, and they see their faith as part of their identity. Their spiritual traditions are so much a part of their culture, it is built into their everyday lives. For example, any feast day of a saint in the Chaldean Church is considered both a religious and a social event. Parish priests of Eastern churches not only represent the Church in their communities, but are also the representatives of the community to the local authorities.

Most Eastern churches have been, or continue to be, minorities in their countries of origin. For some Eastern churches communities, their religious freedom is curtailed by either the political oppression of those countries or the majority religion imposing rules that do not allow the free practice of all religions. The Eastern churches in these countries have suffered with their people, and have always acted as their representative to local authorities; therefore, the communities identify themselves with their particular Church.

Inviting the parish priests of the Eastern Catholic churches to be part of our school life and events would help to strengthen the bonds between families of the Eastern Catholic churches and our Catholic schools. The more those in Catholic schools realise that Eastern Catholic churches parish priests are part of our everyday spiritual and pastoral life, the more we help the families of these churches feel that they are part of our Catholic community.

Our Catholic education vision of honouring the sacred dignity of each person, embracing difference and diversity, and building a culture of learning together (CEM 2016, p. 6), is embraced when we realise that the members of Eastern Catholic churches are a natural part of our community. This also reflects ‘[h]ow the members of the Catholic schools pray, learn, celebrate, belong in community and reach out beyond that community are all expressions of its religious dimension’ (CEM 2017, p. 4).

References

Attwater, D 1935, The Catholic Eastern Churches, The Bruce Publishing Company, Wisconsin.

Catholic Education Melbourne (CEM) 2017, Horizons of Hope: Religious Dimension of the Catholic School, CEM, East Melbourne, accessed 12 April 2021 www.macs.vic.edu.au/CatholicEducationMelbourne/media/Documentation/HoH%20Documents/HoH-Religious-Dimension.pdf.

Catholic Education Melbourne (CEM) 2016, Horizons of Hope: Vision and Context, CEM, East Melbourne, accessed 12 April 2021 www.macs.vic.edu.au/CatholicEducationMelbourne/media/Documentation/HoH%20Documents/HoH-vision-context.pdf.

Ephrem the Syrian 1989, Ephrem the Syrian: Hymns, translated by KE McVey, Paulist Press, New Jersey.

Gorayeb, J 1921, ‘St. Ephrem, the New Doctor of the Universal Church’, The Catholic Historical Review, 7 (3), 303–315, accessed 12 May 2021 www.jstor.org/stable/25011786.

Leo XIII (Pope) 1894, Orientalium Dignitas, The Holy See, accessed 23 April 2021 www.vatican.va/content/leo-xiii/it/apost_letters/documents/hf_l-xiii_apl_18941130_orientalium-dignitas.html.

Paul VI (Pope) 1964, Orientalium Ecclesiarum (Decree on the Catholic Churches of the Eastern Rite), The Holy See, accessed 9 April 2021 www.vatican.va/archive/hist_councils/ii_vatican_council/documents/vat-ii_decree_19641121_orientalium-ecclesiarum_en.html.

Sayegh, M 1963, The Eastern Churches and Catholic Unity, Herder and Herder, New York.

Amer Youhanna can be contacted on 9267 0228 or ayouhanna@macs.vic.edu.au.

Image: St Ephrem.

Source: Catholic Online